Mean value theorem

In calculus, the mean value theorem states, roughly, that given an arc of a differentiable (continuous) curve, there is at least one point on that arc at which the derivative (slope) of the curve is equal to the "average" derivative of the arc. Briefly, a suitable infinitesimal element of the arc is parallel to the secant chord connecting the endpoints of the arc. The theorem is used to prove theorems that make global conclusions about a function on an interval starting from local hypotheses about derivatives at points of the interval.

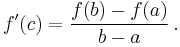

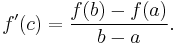

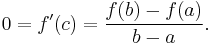

More precisely, if a function f(x) is continuous on the closed interval [a, b] and differentiable on the open interval (a, b), then there exists a point c in (a, b) such that

This theorem can be understood intuitively by applying it to motion: If a car travels one hundred miles in one hour, then its average speed during that time was 100 miles per hour. To get at that average speed, the car either has to go at a constant 100 miles per hour during that whole time, or, if it goes slower at one moment, it has to go faster at another moment as well (and vice versa), in order to still end up with an average of 100 miles per hour. Therefore, the Mean Value Theorem tells us that at some point during the journey, the car must have been traveling at exactly 100 miles per hour; that is, it was traveling at its average speed.

A special case of this theorem was first described by Parameshvara (1370–1460) from the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics in his commentaries on Govindasvāmi and Bhaskara II.[2] The mean value theorem in its modern form was later stated by Augustin Louis Cauchy (1789–1857). It is one of the most important results in differential calculus, as well as one of the most important theorems in mathematical analysis, and is essential in proving the fundamental theorem of calculus. The mean value theorem follows from the more specific statement of Rolle's theorem, and can be used to prove the more general statement of Taylor's theorem (with Lagrange form of the remainder term).

Contents |

Formal statement

| Topics in Calculus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental theorem Limits of functions Continuity Mean value theorem

|

Let f : [a, b] → R be a continuous function on the closed interval [a, b], and differentiable on the open interval (a, b), where a < b. Then there exists some c in (a, b) such that

The mean value theorem is a generalization of Rolle's theorem, which assumes f(a) = f(b), so that the right-hand side above is zero.

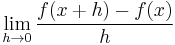

The mean value theorem is still valid in a slightly more general setting. One only needs to assume that f : [a, b] → R is continuous on [a, b], and that for every x in (a, b) the limit

exists as a finite number or equals +∞ or −∞. If finite, that limit equals f′(x). An example where this version of the theorem applies is given by the real-valued cube root function mapping x to x1/3, whose derivative tends to infinity at the origin.

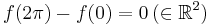

Note that the theorem is false if a differentiable function is complex-valued instead of real-valued. For example, define f(x) = eix for all real x. Then

- f(2π) − f(0) = 0 = 0(2π − 0)

while |f′(x)| = 1.

Proof

The expression (f(b) − f(a)) / (b − a) gives the slope of the line joining the points (a, f(a)) and (b, f(b)), which is a chord of the graph of f, while f′(x) gives the slope of the tangent to the curve at the point (x, f(x)). Thus the Mean value theorem says that given any chord of a smooth curve, we can find a point lying between the end-points of the chord such that the tangent at that point is parallel to the chord. The following proof illustrates this idea.

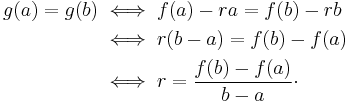

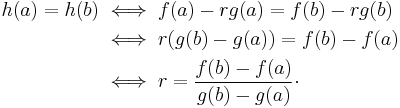

Define g(x) = f(x) − rx, where r is a constant. Since f is continuous on [a, b] and differentiable on (a, b), the same is true for g. We now want to choose r so that g satisfies the conditions of Rolle's theorem. Namely

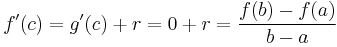

By Rolle's theorem, since g is continuous and g(a) = g(b), there is some c in (a, b) for which  , and it follows from the equality g(x) = f(x) − rx that,

, and it follows from the equality g(x) = f(x) − rx that,

as required.

A simple application

Assume that f is a continuous, real-valued function, defined on an arbitrary interval I of the real line. If the derivative of f at every interior point of the interval I exists and is zero, then f is constant.

Proof: Assume the derivative of f at every interior point of the interval I exists and is zero. Let (a, b) be an arbitrary open interval in I. By the mean value theorem, there exists a point c in (a,b) such that

This implies that f(a) = f(b). Thus, f is constant on the interior of I and thus is constant on I by continuity. (See below for a multivariable version of this result.)

Remarks:

- Only continuity of ƒ, not differentiability, is needed at the endpoints of the interval I. No hypothesis of continuity needs to be stated if I is an open interval, since the existence of a derivative at a point implies the continuity at this point. (See the section continuity and differentiability of the article derivative.)

- The differentiability of ƒ can be relaxed to one-sided differentiability, a proof given in the article on semi-differentiability.

Cauchy's mean value theorem

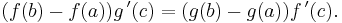

Cauchy's mean value theorem, also known as the extended mean value theorem, is a generalization of the mean value theorem. It states: If functions f and g are both continuous on the closed interval [a,b], and differentiable on the open interval (a, b), then there exists some c ∈ (a,b), such that

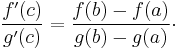

Of course, if g(a) ≠ g(b) and if g′(c) ≠ 0, this is equivalent to:

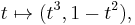

Geometrically, this means that there is some tangent to the graph of the curve

which is parallel to the line defined by the points (f(a),g(a)) and (f(b),g(b)). However Cauchy's theorem does not claim the existence of such a tangent in all cases where (f(a),g(a)) and (f(b),g(b)) are distinct points, since it might be satisfied only for some value c with f′(c) = g′(c) = 0, in other words a value for which the mentioned curve is stationary; in such points no tangent to the curve is likely to be defined at all. An example of this situation is the curve given by

which on the interval [−1,1] goes from the point (−1,0) to (1,0), yet never has a horizontal tangent; however it has a stationary point (in fact a cusp) at t = 0.

Cauchy's mean value theorem can be used to prove l'Hôpital's rule. The mean value theorem is the special case of Cauchy's mean value theorem when g(t) = t.

Proof of Cauchy's mean value theorem

The proof of Cauchy's mean value theorem is based on the same idea as the proof of the mean value theorem.

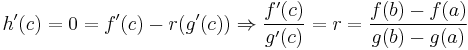

Define h(x) = f(x) − rg(x), where r is a constant. Since f and g are continuous on [a, b] and differentiable on (a, b), the same is true for h. We now want to choose r so that h satisfies the conditions of Rolle's theorem. Namely

By Rolle's theorem, since h is continuous and h(a) = h(b), there is some c in (a, b) for which  , and it follows from the equality h(x) = f(x) − rg(x) that,

, and it follows from the equality h(x) = f(x) − rg(x) that,

as required.

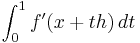

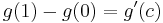

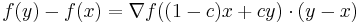

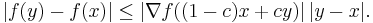

Mean value theorem in several variables

The mean value theorem in one variable generalizes to several variables by applying the theorem in one variable via parametrization. Let G be an open subset of Rn, and let f : G → R be a differentiable function. Fix points x, y ∈ G such that the interval x y lies in G, and define g(t) = f((1 − t)x + ty). Since g is a differentiable function in one variable, the mean value theorem gives:

for some c between 0 and 1. But since g(1) = f(y) and g(0) = f(x), computing g′(c) explicitly we have:

where ∇ denotes a gradient and · a dot product. Note that this is an exact analog of the theorem in one variable (in the case n = 1 this is the theorem in one variable). By the Schwarz inequality, the equation gives the estimate:

In particular, when the partial derivatives of f are bounded, f is Lipschitz continuous (and therefore uniformly continuous). Note that f is not assumed to be continuously differentiable nor continuous on the closure of G. However, in the above, we used the chain rule so the existence of ∇f would not be sufficient.

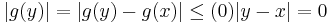

As an application of the above, we prove that f is constant if G is connected and every partial derivative of f is 0. Pick some point x0 ∈ G, and let g(x) = f(x) − f(x0). We want to show g(x) = 0 for every x ∈ G. For that, let E = {x ∈ G : g(x) = 0} . Then E is closed and nonempty. It is open too: for every x ∈ E,

for every y in some neighborhood of x. (Here, it is crucial that x and y are sufficiently close to each other.) Since G is connected, we conclude E = G.

Remark that all arguments in the above are made in a coordinate-free manner; hence, they actually generalize to the case when G is a subset of a Banach space.

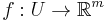

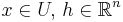

Mean value theorem for vector-valued functions

There is no exact analog of the mean value theorem for vector-valued functions. The problem is roughly speaking the following: If  is a differentiable function (where

is a differentiable function (where  is open) and if

is open) and if ![x%2Bth,\,x,h\in\mathbb{R}^n,\,t\in[0,1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a4bee061b8005588132c5542eb71b684.png) is the line segment in question (lying inside

is the line segment in question (lying inside  ), then one can apply the above parametrization procedure to each of the component functions

), then one can apply the above parametrization procedure to each of the component functions  of

of  (in the above notation set

(in the above notation set  ). In doing so one finds points

). In doing so one finds points  on the line segment satisfying

on the line segment satisfying

But generally there will not be a single point  on the line segment satisfying

on the line segment satisfying

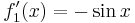

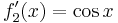

for all  simultaneously. (As a counterexample one could take

simultaneously. (As a counterexample one could take ![f:[0,2\pi]\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^2](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8c53af1b15f29ad6a0fdc7f2c0d2ab1f.png) defined via the component functions

defined via the component functions

. Then

. Then  , but

, but  and

and  are never simultaneously zero as

are never simultaneously zero as  ranges over

ranges over ![\,[0,2\pi]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e3650c52525c5c564cbb7db68fa2740c.png) .)

.)

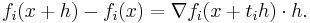

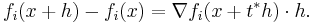

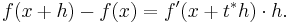

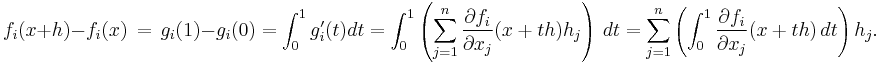

However a certain type of generalization of the mean value theorem to vector-valued functions is obtained as follows: Let f be a continuously differentiable real-valued function defined on an open interval I, and let x as well as x + h be points of I. The mean value theorem in one variable tells us that there exists some  between 0 and 1 such that

between 0 and 1 such that

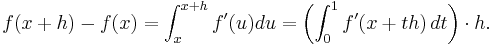

On the other hand we have, by the fundamental theorem of calculus followed by a change of variables,

Thus, the value  at the particular point

at the particular point  has been replaced by the mean value

has been replaced by the mean value  . This last version can be generalized to vector valued functions:

. This last version can be generalized to vector valued functions:

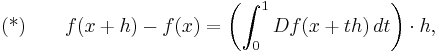

Let  be open,

be open,  continuously differentiable, and

continuously differentiable, and  vectors such that the whole line segment

vectors such that the whole line segment  remains in

remains in  . Then we have:

. Then we have:

where the integral of a matrix is to be understood componentwise. (Dƒ denotes the Jacobian matrix of ƒ.)

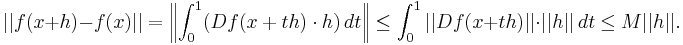

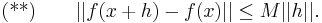

From this one can further deduce that if ||Dƒ(x + th)|| is bounded for t between 0 and 1 by some constant M, then

Proof of (*). Write  (

( ) for the real valued components of

) for the real valued components of  . Define the functions

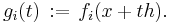

. Define the functions ![g_i:[0,1]\rightarrow\mathbb{R}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ca7a53fe3412b5430f71e1ad6cbf0bfa.png) by

by

Then we have

The claim follows since  is the matrix consisting of the components

is the matrix consisting of the components  , q.e.d.

, q.e.d.

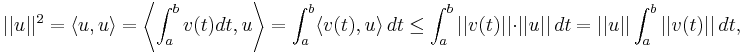

Proof of (**). From (*) it follows that

Here we have used the following

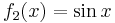

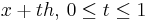

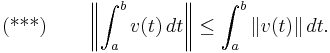

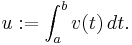

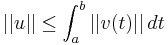

Lemma. Let ![v:[a,b]\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^m](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a628ee97c47c06409c6977f092e2be95.png) be a continuous function defined on the interval

be a continuous function defined on the interval ![[a,b]\subset\mathbb{R}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a54f51b0256823149bb71b71fddcdb70.png) . Then we have

. Then we have

Proof of (***). Let  denote the value of the integral

denote the value of the integral  Now

Now

thus  as desired. (Note the use of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.) This shows (***) and thereby finishes the proof of (**).

as desired. (Note the use of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.) This shows (***) and thereby finishes the proof of (**).

Mean value theorems for integration

First mean value theorem for integration

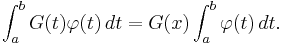

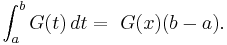

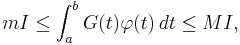

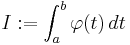

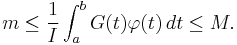

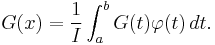

The first mean value theorem for integration states

- If

![G:[a,b]\to \mathbb{R}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f8ee3185589700f86a4febd31d9b2b3d.png) is a continuous function and

is a continuous function and  is an integrable function that does not change sign on the interval

is an integrable function that does not change sign on the interval  , then there exists a number

, then there exists a number  such that

such that

In particular, if  for all

for all ![t \in [a,b]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c9ef8c742260828c469822e9c5dbe2c9.png) , then there exists

, then there exists  such that

such that

The point  is called the mean value of

is called the mean value of  on

on ![[a, b]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.png) .

.

Proof of the first mean value theorem for integration

It follows from the extreme value theorem that the continuous function G has a finite infimum m and a finite supremum M on the interval [a, b]. From the monotonicity of the integral and the fact that m ≤ G(t) ≤ M, it follows that

where

denotes the integral of  . Hence, if I = 0, then the claimed equality holds for every x in [a, b]. Therefore, we may assume I > 0 in the following. Dividing through by I we have that

. Hence, if I = 0, then the claimed equality holds for every x in [a, b]. Therefore, we may assume I > 0 in the following. Dividing through by I we have that

The extreme value theorem tells us more than just that the infimum and supremum of G on [a, b] are finite; it tells us that both are actually attained. Thus we can apply the intermediate value theorem, and conclude that the continuous function G attains every value of the interval [m, M], in particular there exists x in [a, b] such that

This completes the proof.

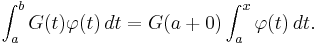

Second mean value theorem for integration

There are various slightly different theorems called the second mean value theorem for integration. A commonly found version is as follows:

- If G : [a, b] → R is a positive monotonically decreasing function and φ : [a, b] → R is an integrable function, then there exists a number x in (a, b] such that

Here G(a + 0) stands for  , the existence of which follows from the conditions. Note that it is essential that the interval (a, b] contains b. A variant not having this requirement is:

, the existence of which follows from the conditions. Note that it is essential that the interval (a, b] contains b. A variant not having this requirement is:

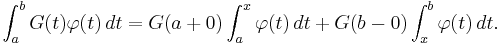

- If G : [a, b] → R is a monotonic (not necessarily decreasing and positive) function and φ : [a, b] → R is an integrable function, then there exists a number x in (a, b) such that

This variant was proved by Hiroshi Okamura in 1947.

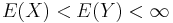

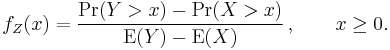

A probabilistic analogue of the mean value theorem

Let  and

and  be non-negative random variables such that

be non-negative random variables such that  and

and  (i.e.

(i.e.  is smaller than

is smaller than  in the usual stochastic order). Then there exists an absolutely continuous non-negative random variable

in the usual stochastic order). Then there exists an absolutely continuous non-negative random variable  having probability density function

having probability density function

Let  be a measurable and differentiable function such that

be a measurable and differentiable function such that ![E[g(X)]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8142e63ac46e012af64f4746a316bd4c.png) and

and ![E[g(Y)]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/08a42476b0720d4492fc7a121b025b03.png) are finite, and let its derivative

are finite, and let its derivative  be measurable and Riemann-integrable on the interval

be measurable and Riemann-integrable on the interval ![[x,y]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8ca042e8ff30aba99a78e069db08b58a.png) for all

for all  . Then,

. Then, ![E[g'(Z)]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8b38be47f656d09e9d71684008cbd64c.png) is finite and[3]

is finite and[3]

See also

Notes

- ^ Weisstein, Eric. "Mean-Value Theorem". MathWorld. Wolfram Research. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Mean-ValueTheorem.html. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ J. J. O'Connor and E. F. Robertson (2000). Paramesvara, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- ^ A. Di Crescenzo (1999). A probabilistic analogue of the mean value theorem and its applications to reliability theory. J. Appl. Prob. 36, 706-719.

![\begin{array}{ccc}[a,b]&\longrightarrow&\mathbb{R}^2\\t&\mapsto&\bigl(f(t),g(t)\bigr),\end{array}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/059563ccca7a1c978c8fc6d8ad4abcfd.png)

![{\rm E}[g(Y)]-{\rm E}[g(X)]={\rm E}[g'(Z)]\,[{\rm E}(Y)-{\rm E}(X)].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2986d39dbc3b25b9dbb247624e2d97ec.png)